When you were a kid, did your parents ever regale you with terrifying stories of what happens to “naughty children”?

When you were a kid, did your parents ever regale you with terrifying stories of what happens to “naughty children”?Yeah, mine too. And some of them were pretty inventive.

But I don’t think even my parents could have come up with a cautionary tale as brutally simple and effective in concept as ‘Battle Royale’.

Japan, early twenty-first century: society is fragmenting; unemployment is rife; youth are disaffected. Entire classes skip school on a whim. Teachers are knifed in corridors. Adults are afraid of the new generation. This – if the work of Harmony Korine is anything to go by – would constitute the norm in an American high school. Evidently, the Japanese authorities take a more extreme view and the Battle Royale Act is passed, a statute that’s part response to the rising tide of adolescent lawlessness, part thinning out of the troublesome generation and part media entertainment.

It’s apposite that I’m working my way through a line-up of exploitation movies at the moment, because (a) ‘Battle Royale’ has a narrative hook that Roger Corman is probably still kicking himself for not thinking of first; and (b) director Kinji Fukasaku made a name for himself with a series of crime, vigilante and Yakuza films.

It’s apposite that I’m working my way through a line-up of exploitation movies at the moment, because (a) ‘Battle Royale’ has a narrative hook that Roger Corman is probably still kicking himself for not thinking of first; and (b) director Kinji Fukasaku made a name for himself with a series of crime, vigilante and Yakuza films.Having directed sections of ‘Tora! Tora! Tora!’ after 20th Century Fox removed original choice Akira Kurosawa from the Japanese half of the production, Fukasaku hit his stride with 1973’s ‘Battles Without Honour and Humanity’ (which lent its title to the instrumental piece by Tomayasu Hotei memorably featured in ‘Kill Bill Vol 1’), the success of which led to four sequels. His 1980 apocalyptic sci-fi epic ‘Virus’ was the most expensive production in Japan at the time; it flopped badly. Nonetheless, Fukasaku made another ten films during that decade, then scored another massive box office success in 1992 with the Sonny Chiba vehicle ‘The Triple Cross’. His output slowed somewhat in the 90s, but he saw in the millennium in magnificent style with ‘Battle Royale’. He was 70 when he directed it, he grabbed the attention of a whole new generation of filmgoers and he proved he could be as immediate, provocative and controversial as any other period in his career.

‘Battle Royale’ is based on a novel by Koushun Takami (it was subsequently adapted into a popular manga serialized over four years). Fukasaku was drawn to the material because of its theme of teenage characters betrayed and dealt with violently by the adult world; it resonated with his experiences as a 15-year old in World War II. Drafted to work in a munitions factory with a workforce chiefly comprised of adolescents, he witnessed colleagues and friends dying in a fire; the survivors burrowed under the bodies of those less fortunate. Afterwards they were tasked with removing the corpses. Fukasaku has said in interview that this was when he realized the government were lying about the nature of the war. As a result, he mistrusted adults and authority.

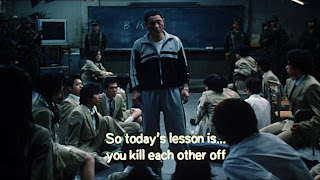

‘Battle Royale’ was made fifty-five years after this formative experience, but it shows in every frame. The story starts with a high-school class drugged during a school trip. They wake up on an uninhabited island under military guard. Their teacher (Takeshi Kitano) informs them they have been selected for that year’s Battle Royale. The rules are simple: they have three days to kill each other. The last kid standing wins. If there’s more than one survivor, the tracking devices that have been clamped round their necks will activate and an explosive charge be detonated. If anyone attempts to tamper with or remove the device: boom! They’re issued with a map, a compass, basic supplies of food and water, a weapon allocated at random (some get guns and crossbows, others a paper fan or a pair of opera glasses) and turned loose on the island to hide, hunt, kill or die.

‘Battle Royale’ was made fifty-five years after this formative experience, but it shows in every frame. The story starts with a high-school class drugged during a school trip. They wake up on an uninhabited island under military guard. Their teacher (Takeshi Kitano) informs them they have been selected for that year’s Battle Royale. The rules are simple: they have three days to kill each other. The last kid standing wins. If there’s more than one survivor, the tracking devices that have been clamped round their necks will activate and an explosive charge be detonated. If anyone attempts to tamper with or remove the device: boom! They’re issued with a map, a compass, basic supplies of food and water, a weapon allocated at random (some get guns and crossbows, others a paper fan or a pair of opera glasses) and turned loose on the island to hide, hunt, kill or die.And that, ladies and gentlemen, is pretty much all there is to say about ‘Battle Royale’. After the preliminaries have been established, what we’re basically treated to is 100 minutes of what happens when 15-year olds are allowed to get stuck in with guns, knives, tasers, scythes, axes and grenades.

What Fukasaku realizes – and this is what keeps ‘Battle Royale’ from being just a well-produced slice of movie violence – is that not all of them will try to kill each other. Some resort tearfully to suicide rather than take arms against their friends. Some hole up and try to rely on each other, even as the pressure mounts and suspicions come to the fore. Some try to fix upon a way of striking back and/or escaping the island.

What Fukasaku realizes – and this is what keeps ‘Battle Royale’ from being just a well-produced slice of movie violence – is that not all of them will try to kill each other. Some resort tearfully to suicide rather than take arms against their friends. Some hole up and try to rely on each other, even as the pressure mounts and suspicions come to the fore. Some try to fix upon a way of striking back and/or escaping the island.But always there are rogue elements. Two exchange students with hidden agendas are introduced into the contest. Some of the kids panic and cause others’ deaths and their own as a result. Some use the extraordinary circumstances to settle petty rivalries or indulge their darker whims. The scariest element of the often brutal vignettes Fukasaku presents is how accurately his 15- and 16-year old protagonists function as a microcosm of the wider adult society in all its vicious and hypocritical glory.

‘Battle Royale’ is the work of an artist at the end of his career who never forget the lessons or experiences of his youth. An established filmmaker who kicked against the establishment. A man who was old and wise but still angry at the way of the world. Fukasaku described the film as a fable. And it’s true: he doesn’t moralize, he doesn’t make a point. He doesn’t fob his audience off. He doesn’t bullshit. ‘Battle Royale’ is a dark and violent fantasia, often funny in the way only the most absurd and satirical humour can achieve. It’s also deeply felt, deeply personal and coruscatingly honest.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar