I’ll be resuming the Winter of Discontent tomorrow (stay tuned, Christina Lindberg fans), but for today – and with mixed feelings – here’s the film that is simultaneously Kinji Fukasaku’s swansong and his son Kenta’s debut.

Made (and set) three years after ‘Battle Royale’, the sequel entered production while Kinji Fukasaku was suffering the final stages of his battle with cancer. He directed one sequence, a flashback featuring Takeshi Kitano, and entrusted the remaining film to his son. Kudos to Kenta Fukasaku for giving his father the stand-alone credit “a Kinji Fukasaku film” above the title and saving his co-director’s credit until the very end.

Made (and set) three years after ‘Battle Royale’, the sequel entered production while Kinji Fukasaku was suffering the final stages of his battle with cancer. He directed one sequence, a flashback featuring Takeshi Kitano, and entrusted the remaining film to his son. Kudos to Kenta Fukasaku for giving his father the stand-alone credit “a Kinji Fukasaku film” above the title and saving his co-director’s credit until the very end.Kinji Fukasaku left a statement before he died, which is included among the DVD’s special features. It starts: “Once upon a time, I spent my youth in the burned-out rubble created by adults. Today, across the oceans, burned-out rubble proliferates by the day, and the hell fires of bombs, dropped in the name of ‘justice’, ravage the next generation. It is always the children who are sacrificed. What can I leave the children of country, blessed as they are with everything but hope?”

Given the hard-won humanity inherent in this statement – and with all due respect to Kenta Fukasaku for having the courage and passion to complete his father’s work while dealing with the terrible grief of losing him so early into filming – it almost seems wrong to criticize ‘Battle Royale II: Requiem’.

In the interests of fairness, and with the proper respect to the father/son Fukasaku team, I’m invoking Robert Browning’s statement that “a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” Although flawed, ‘Battle Royale II’ isn’t wanting for ambition, ideas or balls-to-the-wall fearlessness. Although punctured occasionally by aesthetic misjudgements, uneven pacing and one-dimensional character sketches, it’s nevertheless a film that was created for the right reasons and isn’t afraid to stir some shit, fling some mud and raise an unapologetic middle finger to the establishment.

In the interests of fairness, and with the proper respect to the father/son Fukasaku team, I’m invoking Robert Browning’s statement that “a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” Although flawed, ‘Battle Royale II’ isn’t wanting for ambition, ideas or balls-to-the-wall fearlessness. Although punctured occasionally by aesthetic misjudgements, uneven pacing and one-dimensional character sketches, it’s nevertheless a film that was created for the right reasons and isn’t afraid to stir some shit, fling some mud and raise an unapologetic middle finger to the establishment.The set-up (SPOILERS if you haven’t seen the first film) is this: three years after Nanahara (Tatsuya Fujiwara) and Noriko (Aki Maeda) escaped the island at the end of ‘Battle Royale’, Nanahara has returned from a period of exile in Afghanistan. He’s established himself on another island – Hashima Island (also known as Battleship Island and Ghost Island, it’s located just off the coast of Nagasaki) – and formed a terrorist group who have declared war on all grown-ups. The terrorist group is called the Wild Seven, a pretty fucking cool name that’s even cooler if you’re a Peckinpah or Kurosawa fan.

The Japanese authorities – under mounting pressure from America – target the Wild Seven after a terrorist attack on a major city. If ‘Battle Royale’ was a response to an increase incidence of teenage disaffection in Japan, an early scene in the sequel of two tower blocks crumbling under an explosion makes an unequivocal statement that the remit has widened. It doesn’t matter that all the characters are Japanese, the ravaged city is Japanese, the rebels are Japanese and the military are Japanese; this is explicitly a film about America.

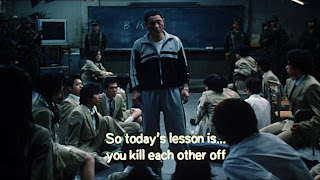

The Japanese authorities – under mounting pressure from America – target the Wild Seven after a terrorist attack on a major city. If ‘Battle Royale’ was a response to an increase incidence of teenage disaffection in Japan, an early scene in the sequel of two tower blocks crumbling under an explosion makes an unequivocal statement that the remit has widened. It doesn’t matter that all the characters are Japanese, the ravaged city is Japanese, the rebels are Japanese and the military are Japanese; this is explicitly a film about America.Rather than storm Nanahara’s stronghold themselves, the military take advantage of the newly passed Battle Royale 2 Law (which – allegory alert – is sneaked through after the terrorist atrocity) to violently coerce a group of adolescents into doing their dirty work. In what plays out as a (deliberate) retread of the first half hour of ‘Battle Royale’, a group of kids heading off for a Christmas vacation are drugged during their coach journey and wake up as they’re entering a Guantanamo Bay style military complex. Explosive monitoring devices are strapped round their necks. The choice is blunt: a bullet in the head, or get kitted out and stage an assault on Nanahara’s island.

In the first of several instances of upping the ante – and proving that more is sometimes less – a pointless new twist is thrown into the works: with the boys and girls of the class given numbers, if a pupil is killed, tries to escape or tampers with the neck device, not only do they die, their opposite number from the opposite sex has their device detonated. As a result, two kids die at the facility when one refuses to participate, and six getting killed during the landing on Hashima Island means the deaths of twelve of them.

Maybe it’s just me, but this makes no sense. You’ve got these poor bastards in the palm of your hand just by demonstrating that you can trigger collar at any time you want. What’s the point in killing pairs of them? If your coerced forces are decimated so badly just securing the beach-head, surely you’re slashing the likelihood of a successful operation against Nanahara by rigging it so that said casualties are automatically doubled?

Maybe it’s just me, but this makes no sense. You’ve got these poor bastards in the palm of your hand just by demonstrating that you can trigger collar at any time you want. What’s the point in killing pairs of them? If your coerced forces are decimated so badly just securing the beach-head, surely you’re slashing the likelihood of a successful operation against Nanahara by rigging it so that said casualties are automatically doubled?The first film dealt with the authorities responding to lawless adolescents by having them kill each other off. Rigging the game by setting a time limit, establishing danger zones across the island and assigning weapons at random some that some kids are destined to die purely because they’ve got fuck all to defend themselves with makes sense given the context. Here, all of these tropes are repeated, but seem at odds with the idea that a bunch of kids are being sent in to kill a more troublesome bunch of kids so that the adults don’t have to get their hands dirty. The exploding collars mean that you can kill off your scapegoats once the mission has been successfully completed. The stacking of the odds against them is illogical.

This is not the only thing that annoys. The attempt to replicate the opening half hour of ‘Saving Private Ryan’ pays homage to just the kind of American aesthetic the film is supposed to be kicking against. Also, the use of “shaky-cam” is so extreme that rather than feeling caught up in the events being depicted, you’re more likely to give up on trying to decipher what’s happening and go off dizzily in search of a travel-sickness pill.

It hardly needs a spoiler alert to make mention of the assault force’s eventual defection to Nanahara’s group. Not that the ensuing joining of forces against the patriarchal oppressors offers much in the way of catharsis. By this point the film has become a propaganda piece, another move away from its predecessor’s sly and darkly humorous remit towards provoking the audience into thinking for themselves, asking questions and making up their own minds.

It hardly needs a spoiler alert to make mention of the assault force’s eventual defection to Nanahara’s group. Not that the ensuing joining of forces against the patriarchal oppressors offers much in the way of catharsis. By this point the film has become a propaganda piece, another move away from its predecessor’s sly and darkly humorous remit towards provoking the audience into thinking for themselves, asking questions and making up their own minds.Like I said, I feel bad for being critical about ‘Battle Royale II’, but it remains essentially flawed. Still, better a film that aims for something and falls short than a film that doesn’t have a single idea in its head.